I read an article in Mslexia a while ago, by Leone Ross. She asked a question I’ve grappled with for years: is grammar elitist? Should we throw it out the window?

Or are you a stickler for grammar—someone who believes we should not start sentences with “and”, and that we should boldly refuse to split infinitives?

For years, I’ve worried about this. I’ve argued with my mum about it. I’ve been anxious about intimidating or excluding marginalised writers (which is a kneejerk anxiety I have about a lot of things, because I am a well-meaning middle-class straight white woman). I’ve been anxious, too, because, dammit, grammar matters. We’re writing to communicate with Other People, not to masturbate onto a page.

But what does that mean for voices who don’t speak in “standard English”? Or those who haven’t had the kind of education that teaches you what an adverb is and how to use it? How do we make sure everyone is included? That writers from all backgrounds and walks of life have access to the same opportunities?

I mean, that question is a lot, and requires far-reaching societal change—but as far as I’m concerned, as a writer and teacher of writer, we can start by questioning our presumptions and beliefs about “good grammar”.

I’m not talking about letting grammar slide here. Lowering standards in a misguided effort to not intimidate or exclude people isn’t just patronising, it’s nonsensical. This isn’t about “correct grammar”, whatever we decide that is. It’s about language and how we use it. It’s about clarity in communication, about expectations, and about effective storytelling—and to achieve those things, we need to construct sentences that work, that convey our message clearly.

Why do we write if not to tell the truth—or our version of it? And if we’re writing our truth, isn’t it important to write it in our voices? And shouldn’t we take care that we’re understood? Or what’s the point?

Using Your Voice

When I was a teenager, I read A Clockwork Orange. Mostly because I knew the film had been banned, and I was curious. It wasn’t an easy read at first (and not just because of the content and story); Burgess created his own language for his characters and it took a while to learn it.

“There were three devotchkas sitting at the counter all together, but there were four of us malchicks and it was usually like one for all and all for one.”

(You may be surprised to note this use of the word “like”; it’s not a modern grammatical invention. A Clockwork Orange was first published in 1962.)

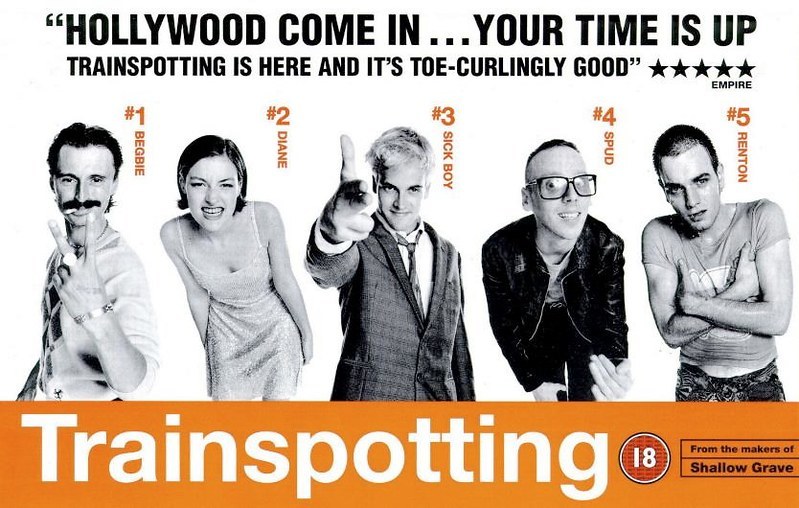

Around that time, I also attempted Trainspotting. I’d seen the movie, of course; so I thought I’d read the book. I’m ashamed to say I never got past the first few pages—it required more work than I was willing to put in at that age, because Irvine Welsh wrote it entirely in colloquial Scottish English using Scottish slang and phonetic spellings of words to create the effect of a strong accent.

If you read it out loud, it becomes clearer… and if you stick with it for 20 pages or so, you get into the swing of things.

“The sweat was lashing oafay Sick Boy; he wis trembling. Ah wanted the radge tae jist fuck off ootay ma visage, tae go oan his ain, n jist leave us."

These books are classics now, and yet at first glance, they’re not at all in “proper English”. They’re not “grammatically correct”. And they’re not easy to read.

Or are they?

(Before you read on, I want to point something out: both these books are very famous, were made into massive films, and were written by middle-class white dudes. I’m sure they had to make their cases to publish them as they are; but it’s worth keeping that in mind. In fact, Irvine Welsh recently said in an interview that he doesn’t think Trainspotting would be published today because vernacular Scots “isn’t commercially viable”. Maybe he’s right.)

Anyway—these books are not in “proper” English.

And yet, they have clarity.

Clarity of thought, idea, expression—and they bring to the story a depth of truth, voice, and place that would be missing if the writers had used the Queen’s English and received pronunciation.

So what to do? Do we worry about grammar, or not? And, the big question: is grammar just elitist?

I grew up in a world where correct grammar matters. It still does matter to me. It sounds right. Or, perhaps it just sounds familiar.

I know there's an argument to be made that insisting on correct grammar is elitist—but that really depends on what your definition of “correct” is.

A Quick Wander Down Grammar History Lane

The English grammar we consider to be correct today started, like so many other rules, with the Victorians. They took a bunch of arbitrary writing ideas and decided this was the correct way to do things.

But language changes, and so do the rules of grammar. If you doubt me, try reading some Shakespeare. And if you want to go back further than that, try Chaucer. Let me know how you get on with that version of English.

(This, by the way, is why the Académie Française is fighting a losing battle with its efforts to preserve the French language unchanged forevermore. It ain’t gonna happen. A language that never changes is a dead language; like Latin.)

So what is “correct” grammar, and “correct” English?

Telling your truth in your words and your language doesn’t mean you throw all the rules of grammar out the window and turn your prose into experimental jazz; it means using your voice and your background to write clearly and precisely. It means making deliberate choices about the words we include and exclude, and the order in which we put them. Every word and its placement should do a job to further the story and deliver the message, or it’s just fluff.

All this may mean using a Scottish dialect, or a Yorkshire dialect, or Cornish, or Jamaican patwa, or AAVE (African American Vernacular English, which is a language of its own), or Valley Girl, or txtspk. These dialects and languages are as dynamic, specific, and disciplined as English; just because they may change faster, or look unfamiliar to the white, middle-class publishing industry, doesn’t mean they don’t follow their own rules of grammar.

And just because it may take a little longer for some of us to get to grips with it—as often happens when we hear a new accent for the first time—doesn’t mean the writing doesn’t make sense. It doesn’t mean the writing is incorrect or sloppy or bad.

Grammar rules are there for clarity, and above all else, I champion clarity in storytelling: can you be understood by the person you’re writing to and for? And does your writing convey the message and the feeling you want it to convey?

We can be inclusive of marginalised writers without allowing sloppy writing to slide by.

We can ask questions of writers about the choices they make with their words and language. We can find sensitive editors who make the effort to understand what we’re doing with our words.

Whatever language we’re using to write, we need to be skilled in it—and that requires learning the rules and practicing. We can throw some of those rules out later, if we want—but every word and phrase and decision we make in our writing should be deliberate. Otherwise it’s a mess.

Reducing “good writing” to “correct grammar” as a small group of people have arbitrarily decided it does everyone a disservice—writers and readers alike. The language becomes bland and floopy, and we lose a depth of voice and experience that can bring a story to life.

As Leone Ross said in her article: “What else is writing, but a way to share the sound of all our worlds?”

Amen to that.

Notes in the Margin

Sign up below for regular emails on creative writing, indie publishing, and the wonders of books.